Peers, Porn and Boys: Communication and Learning of Sexuality in South Africa

|

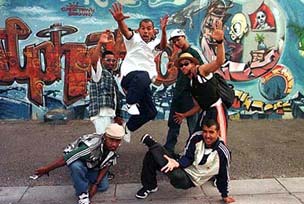

| © Africa

Focus |

Introduction

Listening to young boys talk about sex and sexuality raises the interesting question of how and where they obtain their information. While many studies have noted that peers are a primary source of information on sex and commented on the dangers of this in terms of communicating incorrect information, there is also concern about the lack of information about sex or the appropriate source of information about, which may generate unhealthy outcomes. A young boy narrated his experience in the following terms:

I reckon I was in standard five [when I first learnt about sex], whatever age that is. I gripped [kissed] a chick [a girl] and I told my one mate who is much older than me. I said “hey bro, I kissed this chick.” And then he said “hey bro, do you know about the birds and the bees?” I didn’t know what he was talking about. Then he told me about vaginal penetration and I had no idea what this ou [boy] was talking about. Then a couple of years later, [when I was] about 15, the one oke [boy] got hold of a porno and he was like “hey, let’s check this video”. And then I realised that hey, the thing [penis] actually goes inside (Peter)

When young men discover sex through peers and pornography, they are often left to make sense of the ‘mechanics’ of it all by themselves. Not only does this have major implications for HIV prevention but it may also shape how young men come to understand masculinity.

This article draws on interviews conducted with six young men between the ages of 18-24 years. The research was part of a larger study on sexual and reproductive health in the life worlds of South African men conducted by the Center of AIDS, Development, Research & Evaluation (CADRE).1 We have chosen to report on this particular age group because findings from the study suggest that, despite the development of the new “Life Orientation” curricula in schools, and mass media HIV prevention campaigns, peers and pornography remain the primary sources through which young men learn about sex and the communication of sexuality.

While the article is exploratory and is based on a few interviews, it does however suggest that peers and pornography have been critical in the development of young men’s sexuality. Furthermore, it suggests that young men do not have adequate information about the act of sex prior to experimenting sexually. These findings have implications for the development of HIV prevention initiatives that may successfully target young men.

The “Open Communication” Agenda: Formal And Institutional Structures For Communicating And Learning About Sexuality

A key priority for HIV prevention initiatives in South Africa in the last two decades has been to provide sexuality education to young people. In the late 1990s, “Life Orientation” was introduced in all South African schools as part of the new Outcomes-Based Education (Nakabugo & Sieborger, 2001). Life Orientation provides learners with information about social problems, health and prevention. 2 “Health Promotion,” one of the modules of Life Orientation, specifically addresses issues regarding HIV/AIDS prevention.

Outside of schools, mass media campaigns, non-government organisations, faith based organisations, churches, nurses, community health care workers and families have, in various ways, provided information to young people on HIV prevention.

One of the organisations particularly dedicated to providing sexuality education to young people is called LoveLife. The organisation was founded in 1999. At its inception, LoveLife had the ambitious goal to halve the HIV infection rates among young people aged 12-17 years old in five years (1999-2004). “They proposed that this could be done through initiating ‘more open communication about sex, sexuality and gender relations” and subsequently encourage behaviour change among young people (Harrison et al 2010). However, this has not happened. Despite a total of 92.5% of the population being reached by national HIV/AIDS communication programmes, according to the 2006 National HIV/AIDS Communication Survey, HIV prevalence among young people in South Africa remains one of the world’s highest and young people remain the group most vulnerable to new HIV infections.

Kelly and Ntlabati (2002) write that there is a great need to better understand early adolescent sexual activity in South Africa as a foundation for engaging in HIV prevention programme development among youth. Bhana and Pattman point out that “currently, we know very little about the world inhabited by young adults, how they see themselves, what they wish for, their desires and passions, their fears and the ways in which the performance of masculinities and femininities are constructed, how it is advantageous and how it can inhibit other potential experiences and how it is vulnerable to disease” (2009: 69).

Intimate Exposure: Peer Learning About Sex in Young Age

All the six young men interviewed spoke about learning about sex through friends who were a couple of years older or older brothers. For instance, Jabulani a 23 year old Pedi man living in Johannesburg recalled that that he knew that he needed to have a girlfriend just like his older friends who already had girlfriends. Nkosinathi, a 24 year old male, who grew up in Ulundi, KwaZulu-Natal, learnt about sex through accompanying his older friends to visit their girlfriends.

I grew up having friends who were older than me. So at that time I was in grade 7....They were about one or two years older. Basically I grew up with people who were older than me. So I knew about dating girls and stuff. But then I had not yet developed those feelings at the time. By just dating a girl I was happy, but not to have sex with her. By just meeting her and kissing that was enough, I did not have such strong feelings. But I knew it that as a boy I had to date. That is how I found out that a man and woman should unite. (Jabulani)

While I was growing up, I used to like soccer, I played soccer and everything, and I had friends who were exposed to dating at that age. When they went to check their chicks, I went with them and sometimes obviously at night in boarding school you would see people kissing and everything, and something just happened and I said okay, maybe I have to try it as well. (Nkosinathi)

Both Nkosinathi and Jabulani discovered sex through their friends who had girlfriends and they decided that they too should have girlfriends. Lionel, a “coloured” male living in Cape Town spoke about the pressure to conform to what his peers were doing. The pressure, according to him “did contribute to an extent, actually in a big way contributed to my first sexual intercourse … for me it was a learning curve.”

Sometimes the boys were not eager or voluntary learners, but they learned from their peers through pressure anyway. Richard, an English male living in Johannesburg spoke about how he was introduced to sex and put off sex by his brother.

I didn’t really want to have.... I knew I was just a bit too young

One of the communication tools was the use of stories, perhaps even tall tales about sexual excapades. Richard would recall that his brother would always tell him “all these stories about all these girls he’s got and had.”

Media and Porn

Aside from peers, the other source of information about sex and sexuality for young men was the media, and porn, in particular. In fact for some men, media was the single most important source of learning about sex.

Yah, there was a TV at home... there was a movie called uFix....Fix and Xola, that is they are lovers, so when I was watching that movie at that age and at that time, you will see of love, you will see of kissing, you will see of people maybe under the blanket, so my brain my mind would be thinking that they are doing sex, you see. So I knew that there was no sex without going under the blanket. So I came to understand that if I too want to do sex, that first things is I’m gonna go in the bed, you see, with the girl that I love, you see, ya, thereafter that gooi gooi [quick quick], do some sex, you see, no sex without bed, you see (Yongama).

Peter had similar “education” through “thumping under the blanket” scenarios on the TV when he was “about 14, 15.” His supplementary “education” came from seeing dogs in the streets and trying to cross-match what he saw of the dogs with what he didn’t quite see under the blanket on TV.

However, all the informants were, at some point, exposed to pornographic films or magazines before they experienced sex themselves. Both Jabulani and again Peter attest to this exposure as one of their concrete learning experiences which also activated sexual feelings in them.

And then you hear stories of mates boning cherries on the beach and thumping two chicks at once and you’re like jis, I want to do that. You think that is the best thing ever, and then you watch more and more pornos and look at more and more pornos and yeah, I can’t wait until I get this. You watch it [pornographic films] and your head nearly blows off your penis because all you want to do is do what they are doing on TV. Peter)

While watching pornography and listening to stories from peers gave these young men certain ideas about sex, these ideas did not particularly match what the actual experience of sex would be like. For all the young men, what happened at their sexual debut was different from what they had expected. Sometimes there is a feeling of guilt. Lionel confessed that although he was “desperately looking forward to it,” and when it happened it was “very interesting”, it also left me him “feeling guilty.” For some others, like Peter, it was an anti-climax as it appeared stupid, boring:

…the first time I went down on her and she went down on me. I was like eish, I don’t know if this is right. It’s crazy, but it was nice, so you just carried on until the sex part. I was like this is stupid, boring. Obviously you were laaities [young] you didn’t know what you were doing. … [Sex] But it was Kak! Jis bro, I thought it was the most overrated thing I had ever experienced. I expected there to be fireworks and lightning bolts… It was two okes [guys] having no idea what they are doing. One is going out, the other one is going in. It was like trying to dance with someone and you kept on standing on their feet…. I was like is this what all the stories are about?... I’m like come on, it’s got to be more than this!

From watching pornography, seeing women and hearing the vocalisation of pleasure, Jabulani said he did not understand why women would agree to sex if they were in pain. After his first sexual experience however, he realised this was not the case:

At first I thought that she was feeling pain because she was screaming and crying. But then later as time went by I realized that it was not that she was in pain, she was in excitement. Because she came back to me and said let us

do it again. That was where I realized that I was wrong in thinking that I was hurting her. She was actually enjoying and it is natural. (Jabulani)

One implication of this narrative is that communication of sex and the corresponding learning about sex through pornography and through stories from peers did not prepare these young men for their first sexual experience. Lionel greatly anticipated his sexual debut, but he was not prepared for how he would feel afterwards, which in his case, was feelings of guilt and worry about the sexual risks, while, for his part, Jabulani did not yet understand women’s sexuality.

Porn Communication and the Construction of Sexual Identity

Another implication is that from a young age all the participants were aware that sex is intimately tied to a construction of male identity. As Jabulani stated earlier “But I knew it that as a boy I had to date.”Jabulani said that after his first sexual experience, he immediately went to talk to his friends about his performance even though he didn’t know the right words to describe what had occurred. The response from his friends was to quantify his performance – they want to know how many times he ejaculated rather than how he felt inculcating the idea that sex is about about performance and not emotion.

….obviously you have to go back and say to your friends ‘I have done one, two, three.’ They were asking me did you ejaculate? And I didn’t know what that was about. I said yes, and then they said how many rounds? So I said four. I was answering questions about things I didn’t even know what they meant at that time, because obviously there are things called rounds, there are things called cum and ejaculation and all those things. I just answered the questions, but some of the guys could tell this is a lie.

Similarly, 21 year old Yongama from Grahamstown described the shame and inadequacy he felt when reliving his sexual debut experience with his friends who teased him because the girl, and not him, had initiated sex. His friends told him that men must always be initiators of sex and be in control of sexual encounters.

Young men were pressured and told by their peers about sex. Peers also encouraged young men to perform to certain expectations around sex. Exposure to pornography and media reinforced these messages. This does not leave much space for alternative education about or communication of masculine sexualities, or for allowing men to explore and discover their own sexuality.

Conclusion

From the experience of these representative youngsters, there is no doubt that the primary source of concrete information about sex and the communication of sexuality is through peers and pornography. None of the interviewed boys seem to recall any parallel impact on their learning experience from formal and institutional structures of imparting sexuality education. The apparent inadequacy of these structures suggests that they should be strengthened and diversified so that young men could have adequate information about the act of sex prior to experimenting sexually. This article has not concerned itself with the morality of porn itself, but with the fact that porn ‘education’ tends to thrive in a situation of information lacuna. As noted earlier, these findings do have implications for the development of HIV prevention initiatives and programmes that may successfully target young men.

Notes

1 The study used sexual biographies to analyze the subjective, cultural, social and environmental dynamics of male sexual agency and risk. Twenty two sexual biographical interviews were conducted with men and eighteen interviews with women in Grahamstown, Johannesburg, Cape Town and Pietermaritzburg. The sample consisted of both urban and rural participants, from a wide range of cultural backgrounds, and from the ages of 18-79 years.

2 The Life Orientation syllabus deals with four major modules: health promotion, social development, personal development and physical development and movement. Life Orientation classes start as early as Grade R (5 year olds) and progress to Matric (16-19 year olds). Learners have a minimum of two Life orientation periods a week.

References

Bhana, D and R, Pattman (2009). Researching South African Youth, Gender and Sexuality within the context of HIV/AIDS. Development 52 (1):68-74.

Kelly, K and Ntlabati P. 2002. Early adolescent sex in South Africa: HIV intervention challenges. Social Dynamics. 28 (1): 42-63.

Gallant, M. & Maticka-Tyndale E. 2004.School-based HIV prevention programmes for African youth. Social Science and Medicine 54:1337-1351.

Harrison, A., M, Newell., J, Imrie & G, Hoddinott. 2010. HIV prevention for South African youth: which interventions work? A systemic review of current evidence BMC Public Health, 10:102-124.

Nakabugo, M.G. & Sieborger, R. 2001. Curriculum reform and teaching in South Africa: making a “paradigm shift”? International Journal of Educational Development. 53-60.

By Nolwazi Mkhwanazi PhD, Erin Stern and Rethabile Mashale. This article appears in the september 2011 edition of Sexuality in africa magazine and monographs, published by arsrc.

Nolwazi Mkhwanazi is a senior researcher Centre for AIDS Development, Research and Evaluation (CADRE). She is a graduate of the University of Cape Town and the University of Cambridge. Her research focus is on youth, gender and reproductive health issues in Southern Africa

Erin Stern is a research intern at CADRE. Erin has an Msc in Health, Community and Development from the London School of Economics. She is currently registered for a PhD in the school of Public Health at the University of Cape Town. Her thesis will focus on sexual biographies of South African men.

Rethabile Mashale is a research intern at CADRE. Rethabile is completing a Masters degree in Social Policy and Management at University of Cape Town. Her thesis looks at the approaches used by sports for development NGOs in monitoring and evaluating their lifeskills and sports programmes in schools..”

|